On 15 August 2021, the Taliban seized control of Kabul, marking their return to political power and a devastating turning point for the people of Afghanistan. Nearly four years later, the consequences remain profound, within the country and across the world.

As of mid-2025, Afghanistan continues to face a humanitarian crisis: more than half the population requires humanitarian assistance (UN OCHA, 2025), nearly 6.1 million people have been displaced (UNHCR, 2024), and neighbouring countries such as Pakistan and Iran have intensified deportations of those seeking asylum (UNHCR, 2025).

To mark this difficult anniversary, we are highlighting four key shifts that have shaped life for communities from Afghanistan in the four years since the Taliban’s return.

1. A Systematic Erasure of Women’s Rights

Since 2021, the Taliban have imposed devastating restrictions that have erased women and girls from public life, with Afghanistan now the only country in the world where girls are banned from secondary and further education (UNESCO, 2023).

Women are no longer allowed to work in the majority of fields, with rare exceptions such as parts of the health sector (Human Rights Watch, 2023). They are banned from travelling without a mahram (male guardian), from entering gyms, parks, and from most forms of public leisure (UN Women, 2024). In May 2022, it was also decreed that women must cover their faces in public and remain at home unless absolutely necessary (BBC, 2022). In several provinces, women are prohibited from speaking in public gatherings or appearing on television and radio (UN Human Rights Council, 2024).

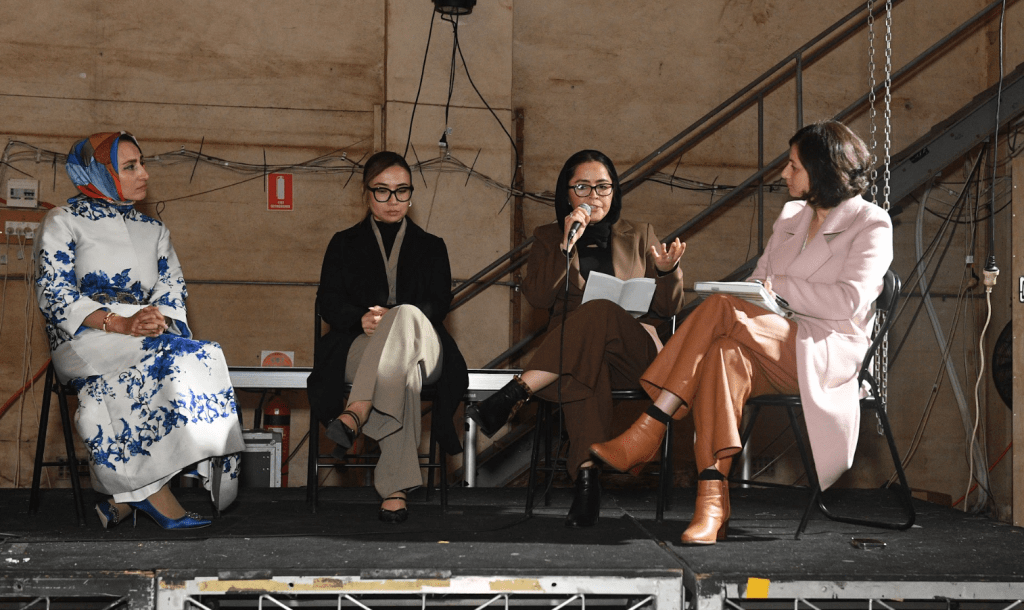

“These policies are not simply social restrictions, they are legalised mechanisms of exclusion,” says Zohal Azra, a lawyer, researcher, and Co-Founder of Huma Media Limited. From Afghanistan herself, and with a deep personal connection to the Hazara community, Zohal warns that “the scale and coordination of these gendered policies amount to a form of gender apartheid”, a term used by human rights groups to describe the institutionalised system of oppression based on gender (Amnesty International, 2024).

Whilst the impact is undeniably harrowing on an individual basis for women, it has also hollowed out vital sections of Afghanistan’s society, including healthcare, education, and civil society, which only served to deepen the ongoing economic crisis.

2. An Escalating Economic Crisis

Since the Taliban’s return, Afghanistan’s already fragile economy has deteriorated further. Due to international sanctions and the freezing of over $7 billion USD in Afghan central bank assets (UNDP, 2024), public services are on the brink of collapse.

Rural communities, which equate to roughly 70% of the population, are particularly vulnerable. Years of drought, rising food insecurity, and declining harvests have left many households without a sustainable source of income or sustenance (FAO, 2024). Women-led households, who are already restricted in their ability to work, are among the hardest hit.

Simultaneously, international aid has decreased. From 2024, the world’s attention has shifted to other global crises, with humanitarian appeals for Afghanistan receiving ‘only a fraction of what’s needed’ to adequately support the country (OCHA, 2025). The result: a growing gap between needs on the ground and the capacity to respond.

3. Forced Returns & Statelessness

In the past year, deportations from Iran and Pakistan have escalated, worsening the refugee crisis. Over 1.2 million people have been forcibly returned so far in 2025 alone, often to places already overwhelmed by poverty and displacement (UNHCR, 2025). Many of those returned have no homes or support networks and face serious risks, particularly minorities, and those with past ties to civil society.

These returns have been caused by ‘internal political pressure, security concerns, and economic hardship in host countries’ (Human Rights Watch, 2024). For example, in Pakistan, a nationwide crackdown on undocumented migrants has led to widespread detentions and expulsions, impacting long-settled families from Afghanistan.

Zohal explains that “the trauma of displacement is ongoing. It doesn’t end upon arrival. Navigating visa precarity, employment barriers, and community rebuilding, all while carrying grief for a country in crisis, is a burden many in the diaspora still bear.”

For those in Australia, especially those on temporary protection visas, the fear of forced return remains a deeply distressing reality.

4. A Cultural Resistance at Home and Abroad

Despite the Taliban’s attempts to erase art, music, and free expression, Afghanistan’s rich culture persists. In Australia, those resettled from Afghanistan are rebuilding their lives whilst simultaneously keeping cultural traditions alive. Food, fashion, and art have become powerful tools of remembrance and resistance.

And whilst several members of the Afghan diaspora remain in limbo, such as the Hazaras featured in Jolyon Hoff’s eye-opening documentary The Staging Post, their determination to rebuild their communities, in spite of ongoing uncertainty speaks to the enduring strength of the people of Afghanistan’s identity.

Take Crochet Things, Farzana Parwizi’s passion-project-turned-thriving-business, showcasing the creative talent of Afghan women. Farzana resettled in Australia after living through the Taliban’s first rise to power. “My small business helped me build confidence in my skills,” she explains. “One day I hope to combine crochet with other cultural crafts to represent my country.”

Other diaspora-led initiatives in Australia include:

- Sakena the Label, a slow fashion brand founded by Afghan-Australian designer Maryam Oria, which highlights traditional embroidery and deadstock fabrics from Afghanistan

- Bamiyan Restaurant in Brisbane, where you can sample the ‘Best of Afghanistan’ through their authentic menu

- Kabul Social, a Sydney-based eatery that provides employment and community for newly arrived refugees; especially women from Afghanistan.

Farzana reflects on the strengths of her national community: “We are hospitable and welcoming. As soon as we’re given a chance to start, we can learn and grow, even if language and cultural differences pose challenges.”

Zohal adds, “Even in exile, creativity lives on. From underground classrooms to diasporic poetry, (we) are finding ways to resist, quietly and defiantly. It’s not just about survival. It’s about expression, dignity, and hope.”

Looking Forward

For refugees and people seeking asylum from Afghanistan, uncertainty persists. Many are still navigating challenging visa systems, work restrictions, and barriers to housing or employment. The trauma of displacement is worsened by the fear for loved ones left behind.

But what has also endured is a powerful cultural identity. Through art, activism, food, education, and storytelling, communities connected to Afghanistan are refusing to be silenced.

Remembrance must lead to action. The crisis in Afghanistan is far from over, but neither is the strength and talent of its people.

Farzana Parwizi is the founder of Crochet Things, a Victorian-based business showcasing handmade creations inspired by embroidery traditions from Afghanistan.

Zohal Azra is a lawyer and Co‑Founder of Huma Media Limited. She works at the intersection of law and storytelling to support displaced communities and cultural resistance.